Rules Must Have Context for Your Autistic Loved One to Understand and Follow Them

“I don’t understand why my 5-year-old son still talks to random strangers even though I’ve TOLD him time and time again not to. Yes, he’s autistic, but he’s verbal and does well in school. I KNOW he understands me. Maybe he’s just being defiant?”

“I’ve told my teenage daughter at least 50 times to lock the door when she comes home, but she never does! I know she’s on the spectrum, but she’s pretty smart, so she must be doing this on purpose!”

Rules That Save Lives

When it comes to autistic people, rules can be difficult. On the one hand, once we learn a rule, it’s often set in stone for us, and even the idea of adapting a rule based on different circumstances or situations doesn’t even enter our heads. On the other hand, if we don’t understand the context of a rule, or the “why” of a rule, we often won’t follow it because it either makes no sense to us, we just can’t remember it, or both.

Take the first example of the 5-year-old autistic boy who talks openly and enthusiastically to strangers. If his mother is neurotypical, she’s likely told him not to talk to strangers again and again because it’s “dangerous” or “not everybody is your friend” or even “they may take you away”.

For a neurotypical child, these are probably valid reasons that make sense, and they will follow the rule. However, for an autistic child, these reasons are just too vague. What’s “dangerous”? What do you mean, “not everybody is your friend?” (How does that even relate to what we’re talking about right now!?) “They may take me away?” Really? To a magical place where nobody misunderstands me!? Yay!

(Not gonna lie. I actually hoped that last one would happen to me when I was a child.)

Instead of wondering if your autistic child is being defiant or willful, assume they need more information if they are not following a rule. Just because the understanding of something is automatic for you doesn’t mean it is for a neurodivergent person.

First of all, in the context of “stranger danger”, it is really important to start by explaining to ALL children, not just autistic, what a stranger actually is.

Instead of saying, “Don’t talk to strangers”, be more concrete. Say, “A stranger is someone you don’t know well. It could be someone you’ve never seen before or even someone you see once in the while like our neighbor down the street. Even if that person is nice to you and waves at you when you get on the bus, they are still a stranger. The bus driver is a stranger. The mail carrier is a stranger. They are all people we see regularly, but we don’t know them. Someone like me, or your dad, or your brother, or your best friend, Todd, or your babysitter, Mrs. Linmore, they are not strangers because they are people we know well and have spent time with for years. We have talked with them and gotten to know them and they know us.”

Once your child has a concrete understanding of what constitutes a stranger and what doesn’t, then move on to explaining why talking to strangers is a bad idea. Remember to give plenty of context and examples, and always check for understanding.

Also, using vague sayings such as, “Not everybody is your friend”, and expecting us to automatically understand your meaning. Instead, explain what that saying means. For example, “When I say ‘not everybody is your friend’, I mean that you assume that all people are good because you’re good, but even if someone smiles at you and talks to you, it doesn’t mean that they have good intentions towards you. Adults don’t usually have long conversations with children they don’t know or offer them gifts or ask them to keep secrets. This may seem nice, but it’s actually a sign that they are not a good adult. This is why it’s important to only talk to people you know and who know you well.”

(No reason to say that word for word, but you get the idea.) Be very specific, allow your child to ask “why” as often as necessary, and explain things that don’t make sense to them, even if you think that the question they asked has to be a joke or an attempt to be rude. It’s not. Autistic people, as a rule, only ask questions to get answers, and receiving those answers is absolutely vital to our understanding of a neurotypical world that was not made for us.

In the second example, an autistic teenage girl keeps forgetting to lock the front door when she comes home from school. Her father has told her over and over again to lock the door, lock the door, lock the door, and, because his daughter doesn’t do it, he ascribes neurotypical intentions to her autistic behavior and assumes she’s doing it on purpose.

Again, she needs more information if she is to make a concrete connection between locking the door and her safety. In addition to being clear, giving context, and answering questions, it’s also very important to make comparisons to something that your autistic loved one can make an emotional and visceral connection to.

For example, “I need you to lock the door when you come home because that’s what will keep you safe. There are bad people in the world who will come into the house and try to take stuff that doesn’t belong to them or even try to take you. Locking the door can keep them from doing that. You know how your brother was always going on your computer until you put a password on it? Well, a lock is like a password for a house. It keeps anyone who doesn’t have the key (the password) out.”

Again, it’s a bit oversimplified, and how you explain anything will depend on support needs, comprehension, circumstances, etc. Just know that context is extremely important, even if you feel you’re “dumbing it down” a bit or being condescending. It’s better to over-explain than under-explain when you’re trying to get your autistic child to follow a rule that is designed for their safety.

A Note on “Because I Said So”

If you’re someone who has been brought up that children should do what adults tell them because you said so, and there’s no reason for an explanation because you weren’t given one as a child, guess what? Autistic people also have no intuitive concept of social hierarchy.

Simply put, the idea that a parent or a teacher or a babysitter have some type of automatic “authority” over us is incomprehensible.

It’s not rudeness or uncaring or blatant disregard of others, the concept is simply not there in most of our heads. To us, everyone is equal from CEO to janitor, and we come into the world like that just as most neurotypical people come into the world with a built-in recognition, respect for, and (sometimes) fear of authority.

That program just wasn’t downloaded into our brains, so “because I said so” is never going to work with us neurodivergent folks. And punishing us for not understanding it only leads to permanent psychological damage; it doesn’t “toughen us up”.

Rules That Save Face

When it comes to social rules, I need an emotional connection to why something is considered socially wrong to understand it and remember to stop doing it.

Most likely, this is the case with your autistic loved one, as well. “You have to thank Grandma for making you dinner because it’s polite” is usually not enough information for us logical, blunt, rigid thinkers. I’m sorry, but when I was a child, if Grandma’s meatloaf tasted like the business end of a dead whale, I would have had no qualms about saying “Ew!” and shoving it away from me (probably too hard and accidentally all the way off the table) in a hurry.

It had nothing to do with hating Grandma or her cooking (I’m just using this as an example), it would have been an automatic and visceral reaction to the incredibly unpleasant sensory experience that was the meatloaf.

I would have had no thought that my behavior was insulting to the woman or that there was ANY connection between not liking someone’s cooking and not liking THEM (that took a while to learn, see Just Because We Don’t Like Your Car Doesn’t Mean We Don’t Like You).

So, if you want to explain to your autistic loved one that it’s impolite to be honest about the taste of someone’s cooking, you have to explain why and give lots of context and examples that will resonate with the way OUR brains are wired.

“You know, when Grandma makes meatloaf and serves it to you, that’s her way of showing you she loves you and wants you to be healthy and well-fed. I know you don’t like the taste of it, but when you tell her that, it hurts her feelings because it makes her feel like you’re physically pushing her and her love away. Remember how you felt when you kept trying to hug Timmy on the playground, and he got mad and shoved you? That’s how Grandma feels when you tell her you don’t like her meatloaf.”

Again, explaining why it’s rude and hurtful is important, but it’s just as important to keep in mind that your child is sensitive to sensory input and that eating something they can’t stand the taste of is the equivalent of you peeling 3-day-old roadkill off the ground and swallowing it whole to prove your love for someone.

Yes, it is that horrible, and nobody who truly cared about you would ever ask you to do such a thing, so remember to see it from both sides always. What’s less harmful? Taking Grandma, a grown adult, aside and explaining what’s happening and risking hurting her feelings for a moment or two, or potentially causing lasting psychological damage to your child by making them choke down the sensory equivalent of 3-day-old roadkill just to “save face”?

Context, context, context, and more context. Autistic people are forever being accused of not “following the rules”, but it’s rarely to do with being defiant or just not caring. We see, process, and move through the world differently, so we need neurotypical life and social rules translated into our language if we are to understand and follow them (or make the autonomous and perfectly valid decision not to when it comes to social rules).

Books for Better Understanding the Autistic Brain

(Whether you’re an autistic person who is newly diagnosed, or you have a loved one on the spectrum, the books below can help you better understand the autistic brain.)

Want downloadable, PDF-format copies of these blog posts to print and use with your loved ones or small class? Click here to become a Patreon supporter!

2 Responses

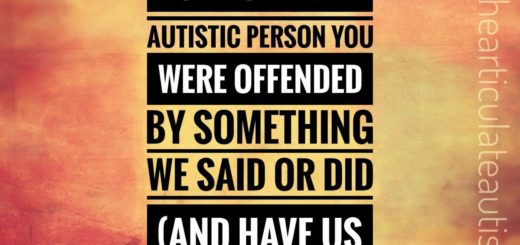

[…] Believe we had no intention of causing any harm and may not even remember what we knocked over or said that you perceived as offensive. This is why it’s so important to reassure us in these moments, and, only when we feel safe and reassured, should you explain what happened (never assume we remember or know what you’re talking about) in detail, why it is perceived as wrong or inappropriate, what feelings you have about what happened, and what we can do to make things right and why we should make it right (give logical, concrete explanations). […]

[…] For Yoru Autistic Loved One To Understando And Follow Them. The Articulate Autistic. Recuperado de (https://www.thearticulateautistic.com/rules-must-have-context-for-your-autistic-loved-one-to-underst…). Traducido Por Maximiliano […]