A Permanent Residence in the Uncanny Valley – Face Blindness From an Autistic Perspective

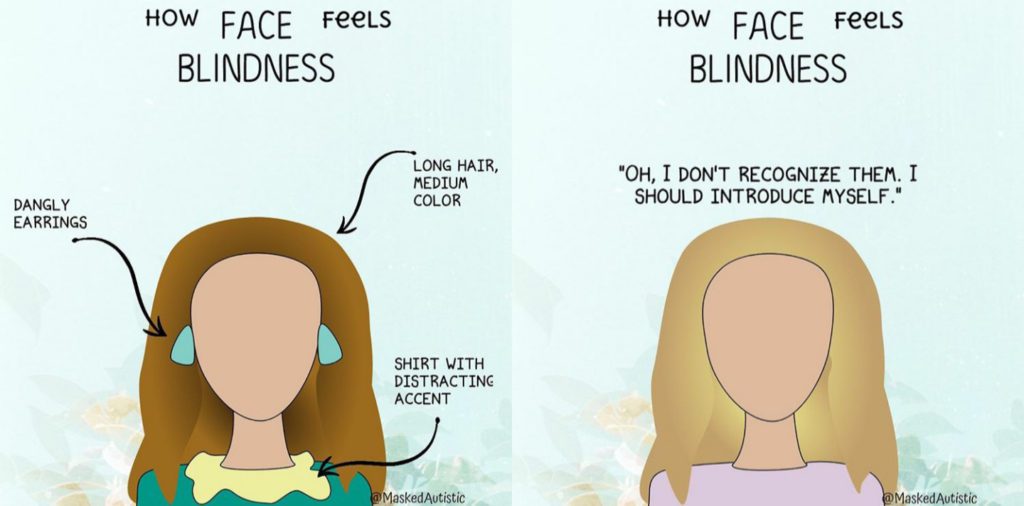

I saw this graphic from The Masked Autistic on Instagram, and she was generous enough to let me use it for this article.

Prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness, is common in autistic and otherwise neurodivergent people. This is just one more factor in how our brains work that can make the neurotypical world confusing and frightening for us.

I have face blindness, but it’s not as significant an issue for me as I know it is for others. Still, I want to tell you my experience in case your autistic loved one struggles with this.

“Hi, My Name is Jaime…Again”

When I was a child, I was told that it’s polite to introduce yourself to others, and I was shown how to do it. Say your name, smile, shake hands, say “It’s nice to meet you”, and all that. When I finally got it down, I was actually very proud of myself for having been able to do it, and, on these rare occasions, it was nice to feel the energy of the people around me relax (instead of tensely anticipating yet another social failure on my part).

It didn’t last.

For one thing, I have terrible working and short-term memory. I mean, it’s BAD. I can forget something I’m doing in the middle of doing it, and my ability to focus is all or nothing. I’m either totally interested and immersed in something, or I don’t care at all. Now, coupled with my mild face blindness, it was a recipe for social disaster.

If I was at a birthday party or other social event my family was having even a day or two after I had already met someone one time, I would re-introduce myself to that person thinking it was my first time meeting them. The relaxed energy that I anticipated feeling from those around me became tense again, and then they got angry with me, thinking that I was mocking the person I had just met only a week earlier.

I wasn’t. They were a stranger to me. One, because of my terrible memory, and two, because of my face blindness. Also, I did not like strangers. I didn’t like anyone I didn’t know coming up to me and trying to have a conversation. I would just walk away. I didn’t even know what “rude” was, I was just trying to protect myself.

So, it didn’t matter if I’d met the person 3 times before, if my brain couldn’t recognize them, they were a stranger and to be avoided. I also wondered why so many “strangers” would walk up to me and talk to me as if they knew me. I think that was the most confusing and disconcerting of all. It was like they had the first few chapters of a book that had been ripped in half, they with the first half, me with the second, and having no idea what happened in the chapters that came before.

A Permanent Residence in The Uncanny Valley

If someone I knew fairly well changed their hairstyle or manner of dress, but their voice seemed the same, that was especially jarring. I remember wondering how a stranger could have the voice of someone I recognized, and it scared me. I’m sure I would stare in abject horror and flounder my words and run away. That was just plain creepy!

Someone’s facial features don’t solidify in my mind until I’ve known the person a while and have spent regular time with them. Once their faces end up in my long-term memory, they’re fine. I will recognize them.

However, if they change their hair from say, long and brown to short and blonde, I won’t be able to place them. I’ll be able to tell from their voice, energy, and mannerisms (now that I understand I have face blindness, a familiar voice coming out of a “stranger’s” mouth no longer scares me), but it will take more than a few seconds for my brain to puzzle it all together.

You know those brain teaser puzzles (Magic Eye) where you’re supposed to stare at a series of dots, and if you let your eyes go limp and slightly cross them, you can see a recognizable image like a car or a dog?

Well, it’s fine to stare at those things for as long as you want in order to get the correct image, but it’s not polite to stare at humans for as long as it takes for someone with face blindness to make a correct image in their mind.

So, that makes it a lot harder for us to puzzle out who you are if you’ve changed your look, especially when you have to do it in the span of seconds to avoid appearing “weird”.

Now, if you change your hairstyle, lose 20 pounds, and shave off your beard, you’re gonna scare the crap out of me when I see you next. I think “uncanny valley” is the best way I can describe it. I know that’s a way to describe human-like qualities in non-human characters (such as robots or avatars) and how off-putting that feels, but that’s the closest I’ve got to explaining what a person with face blindness might feel.

This happened to me with a friend of mine almost 20 years ago now. I hadn’t seen the guy in six months, and we were close friends. Well, when he came over to the house with no beard after having a full one, I just couldn’t get comfortable around him even though the voice was the same, and I knew I knew him. I got used to it, but it was really disconcerting.

How to Help a Person With Face Blindness

- Believe Them

If a person you know and have spent time with says they do not recognize you or walks away from you, believe that the person does not recognize you. Believe that you are a stranger to them. Imagine it this way: How would you feel if a total stranger walked up to you and started asking personal questions about your family as if they knew you but you didn’t know them? Don’t take it personally or as an act of rudeness on the part of the other person. This inability to recognize others is very real, and it can be scary for us.

- Respect Them

Respect the other person’s boundaries, fear, questions, etc. If you see your friend with face blindness out and about, and they appear to ignore you, just let it go. You can always text them later and say, “Hey, I saw you at such-and-such store, and I was wearing such-and-such outfit. I don’t think you recognized me, but I just wanted to say hello.” No pressure, no accusations, no asking how a person you’ve known for 5 years still can’t recognize you in a grocery store (some of us also have trouble recognizing people out of context), just be respectful and understanding.

- Explain With Context

Again, you may know us, but if we have face blindness, we won’t know you, or we may think we know you from somewhere, but we can’t place you for the life of us, and it’s making us very nervous and afraid that we’ll offend you and pay dearly for it (many of us have been verbally and physically abused for acting “rude” towards others even though we truly didn’t know who we were talking to).

Assure the person by telling them exactly who you are. “Hey, Claire. You might not recognize me, but I’m your son’s first-grade teacher, Jennifer Petroski. We met a couple of times and talked about how much your son loves frogs a few months ago. Also, I had longer hair at the time and a different pair of glasses, so I can see where my appearance would be confusing.”

These details are absolutely vital for us in making the connection we need to place you and in relieving our mounting anxiety.

Also, think about the context in which the person would know you. In the case of the first-grade teacher, her explanation worked. However, if you were Claire’s next-door neighbor, describing the house and its location would make things clearer rather than introducing yourself by name.

“Hey, Claire. You might not recognize me, but I’m your next-door neighbor. I live in the blue house on the right side of yours. You usually see me without a shirt on because I’m always in the pool in the backyard. Ha ha!”

Context is very important for autistic and otherwise neurodivergent people as well as those with face blindness.

The Way We Recognize and Categorize Others May Seem Offensive, But That’s Not Intentional

I don’t recognize people by their faces and features first, I never have. Instead, I recognize their energy (my first language is energy, and that is the case with many neurodivergent people), their voice, their walk, their hair, their mannerisms, and their style of dress. I also categorize people based on where I know them from and any distinguishing features they may have.

For example, “library lady with a limp”, “pretty cashier with nose ring”, “Viking guy with long beard and loud laugh”, “man who walks dog and talks to wife on cell phone”, etc.

There actually is a man who walks his dog and talks to his wife on his cell phone in our neighborhood, and I see him all the time, but I would never recognize him if I saw him at the grocery store. In fact, I can’t actually tell you what he looks like other than vague details because his cell phone and his dog are what make him who he is to me. Without those, he’s a total stranger to me!

This is another thing I should probably bring up, autistic people, especially those of us with face blindness, may categorize someone in our minds in a way that may sound offensive if we say it out loud. Some of us are aware of this, some are not.

So, if your autistic loved one says, “The fat lady with the Pekingese” or “The old lady with the camel hump” or “The homeless guy with the greasy hair”, they probably don’t have any intention to offend. For them, it’s just a logical and factual categorization that helps them remember who people are.

Be gentle and patient in explaining why these categorizations may be offensive to others if spoken aloud. Remember, we don’t speak the same language as you, so it may take a while to understand why we can’t just “call a spade a spade”, as it were.

Furthermore, asking an autistic person with face blindness not to refer to the elderly woman down the street as the “old lady with the camel hump” may be faced with resistance because it takes away a fundamental way we recognize others, and that can be frightening.

Take the time to explain why it’s OK to categorize people in your mind a certain way but that saying certain things out loud might hurt the person’s feelings. Furthermore, find a way to compromise on how your autistic loved one refers to others so that they don’t lose yet another way to understand their world and those around them for the sole sake of social graces.

The Takeaway

Believe us, reassure us, don’t take it personally, and remind us. Remember that we are not neurotypical, we are autistic, and the way we process, move through, and understand our world is different from yours. Not purposefully offensive or rude, just different.

Books for Better Understanding the Autistic Brain

(Whether you’re an autistic person who is newly diagnosed, or you have a loved one on the spectrum, the books below can help you better understand the autistic brain.)

Want downloadable, PDF-format copies of these blog posts to print and use with your loved ones or small class? Click here to become a Patreon supporter!

Curious to know if this happens to fellow autistics – I ask someone their name, listen to the answer and all is fine for that interaction

– The next time I see them, I think I know their name but my brain has assigned them a completely different name in the interim

Don’t know if this is a tangential part of face blindness but can’t find anyone else who has this issue.

I can’t remember people’s names or faces, so I relate.

I don’t have face blindness. But I can relate to much of this article because I don’t look at the faces of people I’m directly talking to, and it’s very hard to remember and recognize something you never saw.

Things I have in common with this article:

– I recognize people primarily by their voice. I love people who have distinctive voices because they’re literally easier for me to recognize. I also know well the voices of people I frequently interact with. However, it’s not too helpful if I only see you every other week.

– If you want me to remember you, you need to provide detailed context. Typically, if you can describe in some detail a previous conversation we had, I’ll remember. I love talking, so I remember conversations well.

– I remember and recognize distinctive features that are not located near the face. Distinctive body language? Walk? Shirt? Wallet? Alright, I recognize that! I know who you are! You’re the lady with the big hat! I will not recognize you if you lack this identifying feature.

Things I do not have in common with this article:

– I typically do not notice changes in appearance. I once noticed that my mother had gotten a haircut. When I commented on it, she informed me that she’d gotten it 2 weeks before. I didn’t notice because I recognize my family members so well by their voices and footsteps that I hardly look at them.

– I’m not upset or frightened by changes in appearance. I think this is because the underlying issue is different for me than it is for the author of this article. Their primary method of recognizing people is visual, and it works inefficiently, thus forcing them to resort to backups. For me, my primary method of recognizing people is auditory. I was never trying to glean information through my eyes in the first place, so I don’t get upset when I can’t.

– Due to the above, I seem to be much more successful in navigating social interactions where remembering people is important. I’ve never had the experience of accidentally re-greeting people at a large-ish event. I expect to be remembering people by their voice and my brain is trained by a lifetime of experience to pay attention to the sound of their voice. There is no surprise. I don’t have to scramble. It works efficiently.

It’s amazing how phenomena that appear so similar can have surprising differences that reveal the breadth of human diversity! I’m very glad that this article exists.