A Black Autistic Mother Speaks Candidly About Racism, Intersectionality, and Her Fears and Hopes Around Raising Two Black Autistic Sons

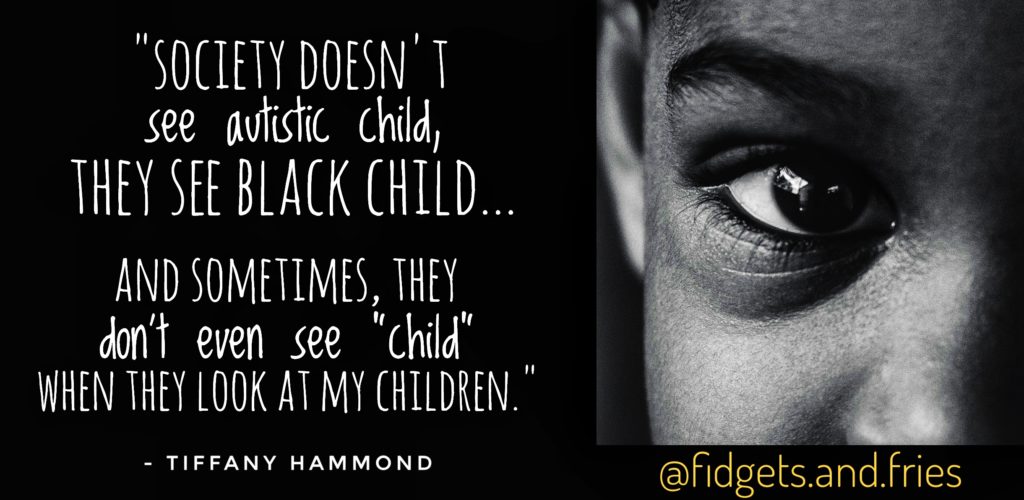

“Society doesn’t see autistic child, they see Black child…and sometimes, they don’t even see “child” when they look at my children.”

– Tiffany Hammond, Fidgets and Fries

Blogger, proud autistic woman, and mom, Tiffany Hammond certainly pulled no punches in this interview, but out of everything she wrote, the quote above stuck with me the most, and it really got me to thinking how horrifying that statement truly is.

At what point in our society do we stop seeing a little Black boy as “cute” and start seeing him as a “threat”? At what point in our society do we stop seeing an autistic person as “different” and start seeing them as “dangerous”?

According to Tiffany from Fidgets and Fries, Black autistic children, especially males, are seen as a threat from an incredibly young age, and this inaccurate perception of them only warps and worsens with time.

This can make simply existing while autistic and Black a minefield to navigate for the autistic person and a cause for constant vigilance, concern, and fear on the part of the parents.

We need to do better, and, in this interview, Tiffany gives us some suggestions on how we might accomplish that.

The Articulate Autistic: Tell us a bit about “Fidgets and Fries”. How did it get its name, and what is the main goal/objective of your blog?

Fidgets and Fries: [For the name], I wanted something fun and catchy. I knew the name had to reflect our personalities. I had two previous blogs, and one was “Glazed Hamm”, and the other was “2 Dollops of Autism.”

The first one was fun and played off our name, but didn’t really inform the reader that it was an autism blog. The second name was also fun, though I felt it was “too much” autism. I outgrew this name, in more ways than one. I no longer wanted to just discuss my children’s autism, but my own, as well. I also didn’t want to just address autism, as I felt I have more to offer the world than that.

It took me some time, but I settled on stuff that we loved a lot. For myself and my youngest, Jojo, we love fidgets. My oldest, Aidan, loves fries. So, Fidgets and Fries. I felt like you could tell it was an autism blog/brand without me feeling as though I needed to be tethered to only autism content. And it’s fun!

[The main objective of the blog is]I want to change people’s perception of autism. I want people to recognize the challenges associated with autism, but to see the beauty of the autistic mind, as well. I want to help the parents who are having a difficult time on this journey and stuck in dark spaces feeling as though they are alone.

Autism needn’t be this lifelong struggle. I want to help parents find their footing on this journey so that they can help their child reach their fullest potential, and not lose themselves in the process.

I also tackle issues of intersectionality. The concept of intersecting identities converging in one individual creating a complex system of oppression.

In other words, autistic individuals have a challenging time just being autistic individuals, but this is further complicated by race, gender, age, etc. I aim to inspire others to look at the specific challenges this minority within a minority faces, acknowledge them, and work to address them so that the needs of all those within this community are met.

I also want to inspire others to want to educate themselves further on the issues that affect those of intersecting identities. I want to inspire thought leaders, those who want to advocate more on behalf of this community.

But ultimately, I want to create a community that is worthy of my children. I hadn’t found one that I felt was inclusive enough for us, and I decided that it was time I created one.

AA: When did you start the blog, and what was your motivation for doing so?

F&F: Fidgets and Fries is “new” this year, but I have been writing for years and blogging for about 3 years now. I always write for me, first and foremost. I write for an audience of one. I am the person I look to impress.

I write because it helps me cope with all that I am faced with. It helps me deal with my emotions and channel my energy. When I saw that my writings helped others, it made me happy, but it didn’t make my day. And it still doesn’t, honestly.

I write because it’s how I make sense of the world. That’s my primary motivation for doing so.

Everything else that comes from this, stems from my writing keeping me grounded and keeping me safe. The day my pen no longer saves me, is the day I will stop everything else that comes from this. My writing helps others because it helps me. People say I have this “big heart” because I help so many people. I don’t know that that is true. I want it to be true. My head fills with so much stuff, I can’t hold it all, and I have to let it out in my work.

I hope my heart is big. I hope that one day I find that my motivation for all of this was truly because I wanted to help so many people who needed it, but sometimes I don’t know. Maybe I will figure it out soon.

AA: As a mom of two Black autistic children, do you believe the color of their skin affected how and when they were diagnosed? If so, what barriers did you face?

F&F: For us, we were fortunate in that there were no delays in diagnosis. My oldest was diagnosed at 17 months. It took one evaluation. He was apparently “obviously autistic.” My youngest was diagnosed at 6 years of age. The delay was in part due to my denial and part due to school officials and family members just stating he “was shy.”

Once I decided that it was time for him to be evaluated, the process took no time at all. I was sure of what I wanted and mindful of the experts I sought for his evaluation.

Our issues with him came from the school who felt he was not autistic, but “emotionally disturbed.” This is definitely something that they often diagnose Black children as instead of autistic.

As someone who spends a considerable amount of time with other Black autistic families, as well as being a Doctoral student who is currently studying race and autism, there are many instances in which diagnosis of Black children (and adults) is difficult to acquire.

Some barriers include: cultural bias within healthcare (many times PCPs will not take the concerns of Black parents seriously and will not provide referrals for evaluations); skepticism within the Black community (if you don’t believe there’s an issue, you won’t do what’s necessary to address it); Black people are not typically involved in research (this could influence why a lot of us aren’t diagnosed sooner or at all because we aren’t represented adequately in the data); cultural biases within research has blinded researchers to autism in the Black community (it’s imperative to address the biases that result in disparate diagnosis and treatment).

AA: Has the fact that your children are Black and autistic caused them to experience mistreatment that you’ve not seen white autistic children experience?

F&F: They have received mistreatment that children who aren’t autistic experience. This is how much race informs our experience.

Society doesn’t see autistic child, they see Black child…and sometimes, they don’t even see “child” when they look at my children.

[My children] experience the most mistreatment because they are Black, not because they are autistic. The autism just makes it harder for them to understand why they are being mistreated because they are Black. The autism just presents itself in a way that others can further justify their treatment of them because they are Black. Our Blackness is the role that most influences all others. We cannot hide it. And others cannot unsee it. We are always Black first.

AA: When were you diagnosed? Do you believe race was a factor in any delay in your diagnosis, or because you are a woman?

F&F: I was diagnosed when I was 18 and a freshman in college. It was suspected when I was around the age of 14 or 15 when I was first placed on depression medication. The clinician stated that he felt I had Asperger’s. I figured that was a fancy way of saying my depression was advanced. We did not pursue this any further and did no further testing. I took my prescription for Paxil and went on my way.

I think that in my case, the race issue was more internalized than externalized. There’s this stigma surrounding mental disorders and developmental disorders in the Black community. I didn’t want to be seen as that “mental” person in the family. I pretty much hid my depression just as I hid the suspicion of Asperger’s.

I had been hiding my whole life. I saw how we treated others with diagnoses. That couldn’t be me. When I finally received a diagnosis, it was pretty quick. I went to Psych Services for another reason but ended up doing an evaluation and testing.

AA: In your opinion, what is the most common misunderstanding you have faced in regard to your boys?

F&F: Collectively? That they don’t understand the world around them. They know more than people give them credit for. Including Aidan, who many feel is “too severe” for comprehension.

AA: Has there ever been an incident where you feared for the lives of your sons because of their race and neurotype?

F&F: Yes, several. Police were involved in many of them, and 95% of these incidents were the result of my boys simply stimming, just being who they are and it making those around them uncomfortable. There were incidents that their father and myself were involved in that we feared because we were detained in such a way that we could not keep them calm and feared their behavior would get them hurt. And there are incidents in which we have to maintain our calm, “contain their autism” so as to not appear threatening so that those who are uncomfortable with our presence do not threaten to call the police or actually do so.

AA: In your opinion, what can people (educators, professionals, law enforcement officials who work with children) do to improve their understanding of neurodiversity, especially among the Black community?

F&F: First and foremost, they need to recognize the differences. Too often people think it rude to point out our differences. To focus on the fact that we are different. This is a mistake. We need people to understand that we are different, in mind and body. And different isn’t bad. Once they can actually see that we are different, they can begin to understand why our specific challenges are unique to just us.

Next, we need more representation. And I don’t just mean bodies placed in neat spaces for optics. I mean we need to have more voices in their spaces that they actually listen to.

There are very few neurodiverse voices in these spaces (law enforcement, education, healthcare, public policy, etc.), and there are even fewer Black neurodiverse voices.

And of the few voices that are there, they serve as little more than props for photo ops. If they want to improve their understanding of neurodiversity, especially as it pertains to the Black community, they must first…recognize our Blackness and all that it means, seek out more of our voices, and actually listen to what we have to say.

AA: Thank you for taking the time for this interview, Tiffany. I appreciate it. Where can we read more of your work and connect with you on social media?

Instagram: @fidgets.and.fries

Facebook: facebook.com/fidgetsandfries

Website: fidgetsandfries.com

Email: fidgetsandfries@gmail.com

1 Response

[…] En las palabras de Madre autista negra tiffany hammond, […]