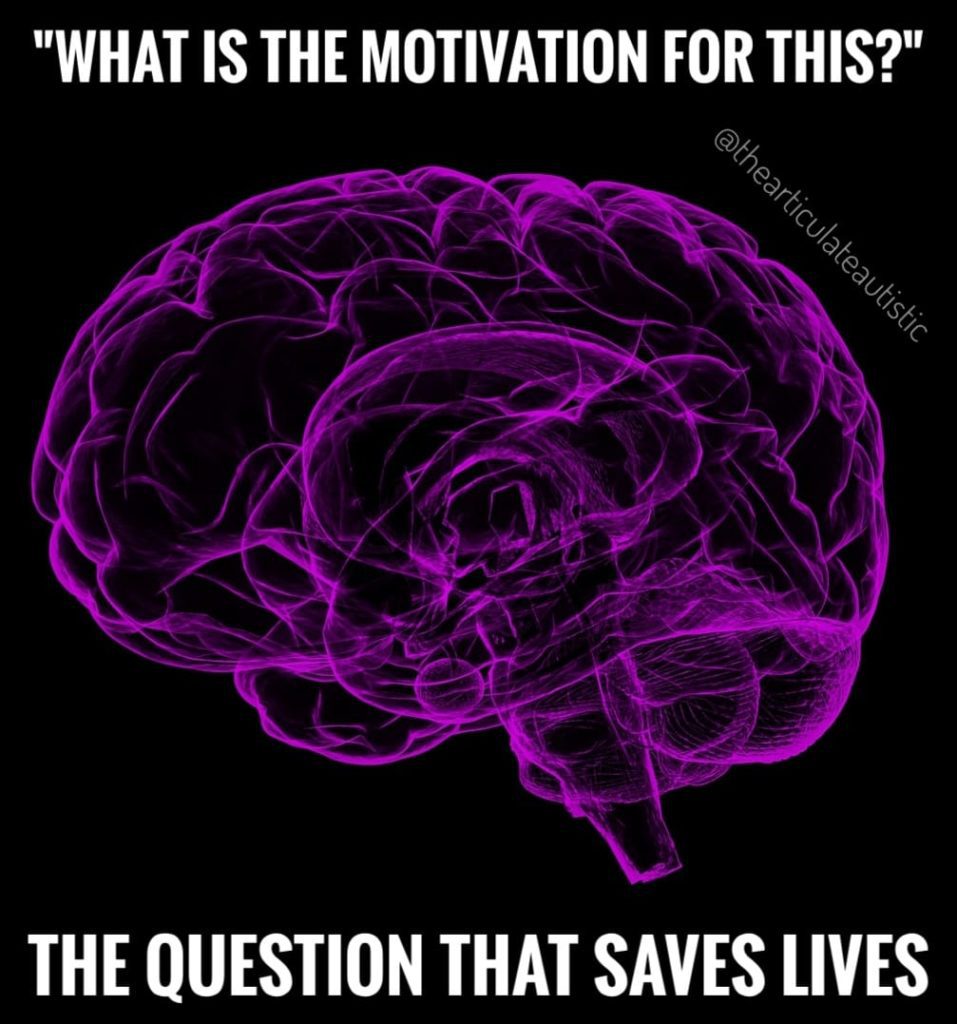

“What Is the Motivation for This?” – The Question That Saves Lives

I like to dissect meanings and words and themes and break them down to their barest essentials, and I think I’ve done that here recently.

My brain has been busy working behind the scenes for clues and connections, and I’ve come up with one I’d like to share:

Reactionary responses are dangerous, no matter the neurotype.

From what I’ve read in the comments on posts I’ve made in the past, some NT (neurotypical, non-autistic) people are highly emotionally reactionary.

That is, the NT has an interaction with someone, they feel an emotion, and they instantly and rather vehemently react to it.

Now, I know many ND (neurodivergent, autistic) people are the exact same way. Granted, it’s for different reasons, but it doesn’t change the fact that it’s true.

So, I think the solution might be as simple as stopping, breathing, and asking yourself, “What is the motivation for this?”

For example, say you’re an NT person with an ND child, and said child just pulled away from you while you were speaking to them and ran up the stairs and slammed the door.

There are any number of reasons this could be happening:

1) Sensory issues; your child was overwhelmed by a smell coming from you (breath, perfume) or the sound of your voice or the feeling of your hands on their arms.

2) Emotional overload. They can’t take one more feeling or thought, or they’re going to melt down, and they have to get away ASAP so as not to accidentally hurt themselves or others.

3) Your child really doesn’t want to do a thing and is expressing that in the only way they can at the moment.

4) They don’t understand what you’re saying and are afraid to say so, so they run.

5) They’re being purposefully disrespectful because they’re angry.

OK, it could be any one of these reasons or none of them, and I could site plenty more.

So, instead of chasing them up the stairs and reprimanding them for running and slamming the door, stop. Wait a minute. Take a deep breath.

“What is the motivation for this?”

This would be a good time to go over your child’s day in your mind. Is it sensory overload? An unmet need? Anger? Hurt? Frustration?

The thing is, you don’t know for sure, and if you jump immediately to disrespect and respond accordingly, a bad situation is going to be made 10 times worse, and nobody is going to get any closer to resolving the issue.

(Article continues below.)

The best way to improve communication with your autistic loved one is to understand how your autistic loved one’s mind works! Intentions, motivations, and personal expressions (facial expressions or lack thereof, body language, etc.), are often quite different in autistic people than they are in neurotypical people.

Experience a better understanding of your autistic loved one by reading books about life from an autistic perspective as well as stories that feature autistic characters. You’ll have so many “Ah ha!” moments and start seeing your autistic loved one in a different light (and you’ll have a better understanding of their behaviors, which you may have been misinterpreting up until now).

Books I recommend for a better understanding of your autistic loved one:

ND people, same concept. Now, I know that because of our neurology, our reactions are quite a bit harder to control. After all, meltdowns aren’t something we do, they are something that happens to us.

However, before we get to the point of no return, we can also wait a minute, breathe, and ask ourselves, “What is the motivation for this?”

Say you’re an ND person with an NT spouse. They said they would swing by to pick you up from work at 5:30, but it’s 6:00, and there’s no sign of them. You call and text, but you don’t get any response.

By the time 6:15 rolls around (if you’re anything like me), they’ve cheated on you, been mugged, been hospitalized, died, came back to life somehow, and they’re just doing this because they KNOW how much it upsets you, and how dare—

And then, they pull up, explain they got stuck in a traffic jam on the highway and accidentally left their phone at work.

Meanwhile, you’re so upset at what was going on in your head, you have a meltdown the entire way home.

Like I said, meltdowns can’t be stopped once they start. An autistic person can’t stop having one any more than a person with asthma can just suddenly stop having an attack.

However, they can be mitigated if we stop, breathe, and ask, “What is the motivation for this?”

I can’t take credit for coming up with this, either. This is a skill I learned from my years in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and it can work for both NDs and NTs, and it just takes practice and patience to learn.

I know it’s much easier said than done, but it can quite literally save lives, not physical lives, but emotional and spiritual ones if both neurotypes make a conscious effort to avoid automatically assuming malice from the other during day-to-day interactions.

Follow me on Instagram.

Want downloadable, PDF-format copies of these blog posts to print and use with your loved ones or small class? Click here to become a Patreon supporter!